Sanderring

New University at Sanderring

A tour of the building's history

“What do you mean, ‘New University’? Surely, that’s the one up at Hubland!” This comment is frequently heard from confused first-semester students new to Würzburg. At first sight, calling the building at Sanderring “Neue Universität” seems to be a misnomer. After all, the imposing building is anything but new – it was inaugurated on 28 October 1896.

First-semester students have their classes at Hubland – they generally only see the inside of the New University during registration and rarely enter the building again. For students, the word “new” is associated with the buildings on the Hubland expansion grounds. Compared to these buildings, the structure at Sanderring clearly is “old”, especially since most students have never heard of the real Old University compound at Domerschulstraße.

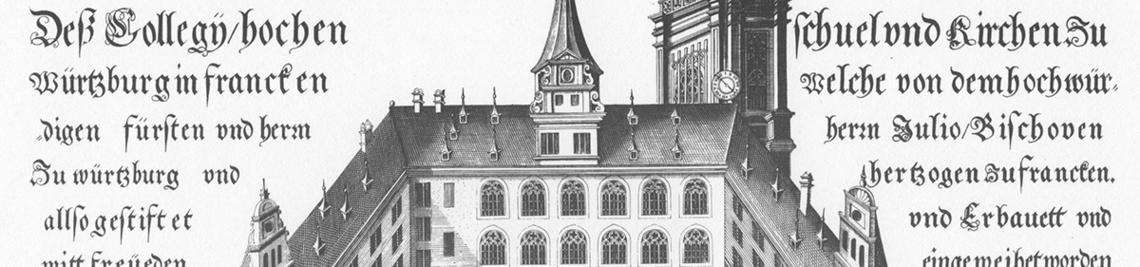

“You only know a thing once you know its history.” There is wisdom in this old saying – and a little history lesson will make it clear to puzzled students why the “new one” is not called the “old one”, despite its age. The first building of the institution of higher education founded by Prince-Bishop Julius Echter von Mespelbrunn was the Old University building on Domerschulstraße. Its construction began in 1582 and was completed nine years later, in 1591. It was a colossal structure by the standards of the time, providing more than enough space for the academic activities envisioned for the institution.

More students – lack of space

Yet the university kept growing, particularly in the 19th century, when interest in medicine and the natural sciences saw an enormous upturn. Space in the university building became scarce. As a result, new institutes were gradually established at today’s Röntgenring. Between 1853 and 1896, the student population almost tripled, from 606 to 1,624. Ultimately, the newly-founded facilities would also prove to be too small. The Main Building, today’s Old University, not only housed classrooms, but also science and art collections, apartments for the Rector and the professors, administrative offices, and the library. It’s no wonder that complaints about the cramped and overcrowded space were getting louder and louder.

Relief came in the early 1870s after the ring of fortifications around the city had been torn down. At that time, the Academic Senate of the university decided to alleviate the space situation with another new building. No one, however, had any intention of constructing a new main building – to abandon the venerable and familiar rooms seemed irreverent. The initial plan was to move university’s book collection to a new home. However, the search for a suitable building site for a library would still take several years.

Books do not need airy rooms

It was determined that the library should be as close as possible to the Main Building, but also situated in a quiet and secluded location that could offer space for future extensions. Various properties were inspected, such as the area between Rennweg and St. Johanniskirche or the site where the District Court Building stands today. But all of these sites were rejected for various reasons, such as aesthetic concerns or political obstacles.

The building site at today’s Sanderring was selected in December 1876. Over the following years, however, the plans were nearly forgotten as other new construction projects seemed to take priority. Eventually, it was Professor Georg Schanz who turned the situation around. During the Senate meeting of 9 March 1885, he proposed converting the old University/the Main building into the library and the Museum of Art History and to erect a new university building on the site intended for the library. Once again, he pointed out the dearth of lecture halls in the Main building of the Old University, their shabby condition, and the loud noise caused by the heavy traffic of horse-drawn carriages in the busy streets around the university. Why should airy and sunny rooms be created for the books, while people were reduced to “pursuing their duties in gloomy and noisy caves”?

The idea was met with approval. Late in 1892, construction began under the guidance of architect Rudolf Ritter von Horstig. Horstig, born in 1858 in Michelbach near Alzenau, had studied Architecture in Munich and had been involved in the construction of the Central Station there. Since 1883, he had been living in Würzburg and became President of the Royal University Building Inspectorate in 1892.

“Words of warm recognition” at the inauguration

The day of inauguration, 28 October 1896, was duly celebrated. In the morning, the academic community assembled at the Old University to bid farewell to the old familiar rooms. The festive procession then made its way to the new building, where the guests of honor were waiting. After the opening ceremony, the program called for a tour of the building, which “inspired words of warm recognition and admiration of the happily achieved marriage of beauty and utility in all those present”, as it reads in a publication of the Academic Senate from 1897 (“The New University Building of the Royal Bavarian Julius-Maximilians University in Würzburg. Its History of Construction and Inauguration”).

However, on 28 October 1896, the structure was not yet finished – the roof of the central part was still bare. The group of statues, designed by Munich sculptor Hubert Netzer, was added only later. It represents Prometheus, brandishing the torch of intellectual progress against the dark powers of Ignorance and Bestiality and for Truth and Justice. The figures are supplemented by a bronze plaque with the inscription “Veritati” – the edifice was to be unmistakably consecrated to Truth. The inscription goes back to Würzburg theologian Herman Schell, then Rector of the University – it was his personal motto.

Busts on the façade

Two busts still adorn the building’s façade today. One represents the second founder of the university, Prince-Bishop Julius Echter, while the other shows Prince-Regent Luitpold of Bavaria. A likeness of the first founder, Prince-Bishop Johann von Egloffstein, presides over the side entrance and looks over Geschwister-Scholl-Platz. Originally, the structure was asymmetrical, the west wing merely a stump compared to its eastern counterpart. Only after an extension was added between 1915 and 1918 did the New University have two side wings of equal size.

By decree of the Senate, the edifice was to be named “New University” – by then it had evolved into more than just a lecturing facility, but would also serve as the new Main Building of the University, complete with all the offices for its self-government. In addition, there were lecturing halls for the Faculties of Theology, Law, and Philosophy, apartments for the janitor and the mechanic in the basement, rooms for the heating units, filing departments, storage areas for coal reserves, and a washhouse.

Even a 175-m2 gymnasium was provided. But where students once engaged in the pursuit of physical fitness, rather the opposite is true today. Students no longer exercise in the gymnasium but rather indulge in their caffeine habits – the former sports facility now serves as a cafeteria. The use of other rooms has changed as well. A former lecture hall on the second floor, for instance, was converted into the office of the university’s President. It was clear to everyone attending the inauguration that the new structure would see many changes in the future. Yet hardly anyone at the festive assembly could have imagined that in less than 50 years, von Horstig’s creation would be reduced to rubble.

Lectures among the ruins

During the bombing raid on the night of 16 March 1945, the New University met with the same fate as the rest of the inner city. Bestiality, against which he was raising high his torch, did not spare Prometheus either – he was left broken and decapitated on ruins. Rebuilding began in the summer of the very same year. Many volunteers, quite a few professors and students among them, helped clear away debris and procure building materials.

In the autumn of 1945, the Faculty of Theology resumed teaching, even if only on a temporary basis. In January 1946, the Faculties of Philosophy and of Natural Sciences followed suit. For today’s students and lecturers, it must be hard to imagine having class on a construction site. The first proper seating was only installed in lecture halls as late as 1949. By the end of 1950, 2.15 million Deutschmarks had been spent on the rebuilding of the New University, as shown by the records of the University Planning and Building Office – an amount corresponding to approximately 10 million euro in our time.

In 1954, it was decided to renovate the Auditorium Maximum, the largest lecture hall, as a “purely functional space” with around 500 seats. One year later, the Audimax was inaugurated. “The new ceremonial space differs from the earlier assembly hall in its sober architectural note, which has replaced the grand marble columns and lavish stucco work that expressed the desire for representation of a bygone era”, noted Main-Post, the local newspaper, at the time. The Audimax has retained its business-like atmosphere until today, excluding the three huge arched windows with integrated doors that provide access to the balconies and allow daylight to flood the space. The great windows might have been a dire necessity to making lectures bearable, as smoking was only banned in the lecture halls in 1963.

A fourth wing for even more students

In 1960, the University Planning and Building Office officially presented the edifice to the university. The next expansion, a fourth wing, was already in the planning stage, for the university kept on growing. In the spring term of 1957, 2,935 students were enrolled. Three years later, the number of students had risen to almost 4,800, and in the summer of 1965, it surpassed 7,000. This was also the year that the foundation stone of the first building on Hubland Campus was laid.

Several models were debated for the fourth wing, which today houses the various Departments of Economics. For instance, the erection of a high-rise structure to annex the west wing was proposed. Eventually, the new wing was designed in such a way that it would connect with the other three wings of the old structure to enclose a huge hall. The hall became known as the Atrium and was used for exhibitions, festivals, and even for sit-ins. Though incidents during the time of student unrest usually occurred at Studentenhaus, the New University also occasionally became a target for protest. In the night of 12 July 1968, stones were thrown at the glass of the main doors. The University Planning and Building Office recorded the damage in photographs, laconically commenting, “12 stones, 10 hits”. At the time, however, it was rumored that the stones had not been thrown by JMU students, but by students from Frankfurt, who had travelled to Würzburg to cause damage.

The old city wall at the parking lot

In order to implement the fourth wing project, the Main Staircase (see photograph) had to be torn down. Würzburg writer, painter, art critic, and monument conservator Heiner Reitberger (1923-1998) published a regretful commentary in the Main-Post, under his pseudonym of “Kolonat”, the name of one of the Guardian Apostles of Würzburg and Lower Franconia: “In the immediate future, something will be demolished, which has always … been one of the best things about the New University, the Main Staircase. Although the Neo-Baroque stucco work that was damaged in the bombing and the firestorm has never been renovated, and the short, urn-crowned pillars holding up the banisters of the stairs between the second and the third floor are missing, as are the original decorative trellises, … on the whole, the staircase still exudes an air of great dignity”.

While the historical Main Staircase was sacrificed for the construction of the annex, another historical structure was gained: When excavating the building pit at the back of the New University, workers struck the remains of the walls of the medieval keep from the 15th century. The ancient city fortifications were partially built up again, eventually being integrated into the extension. They now line both the access ramp down into the underground parking lot and the parking facilities above ground. Reconstruction also included creating somewhat smaller replicas of the semi-circular towers along the wall. Partially overgrown with ivy, the towers lend a special charm to the space between the compound of the Government of Lower Franconia and the New University.

Modern sculpture in the Atrium

The topping-out ceremony for the annex was held in October 1970. Since then, the Atrium has been the spacious center of the New University building. Alcoves in the east and west walls contain statuary and sculptural representations alluding to the university’s goals and its history: Adam and Eve confronting the Tree of Knowledge, and the historical seal of the university facing the Coat of Arms of the Free State of Bavaria. Other works, such as a mobile, symbolize the globe and the city of Würzburg, with its colors of red and gold. Lastly, Julius Echter’s portrait was engraved in stone by Würzburg sculptor Helmuth Weber.

And so, the artworks in the Atrium offer first-semester students a number of clues to puzzle out the difference between the “Old” and the “New” Universities: Beginning with the founder of the Old University, Julius Echter (whose likeness is certain to be familiar to students since it graces the labels of the wheat beer bottles of the local brewery), students can now trace the architectural development of the university. At the end of their quest, they will, as it were, have reached the “Tree of Knowledge”, finally knowing why the New University is not the Old one.

Robert Emmerich