March 1945

The bombing of March 16, 1945

With the attacks on Coventry and London in 1940, the terrorist attacks from the air against civilians, which were to return to their country of origin with horrific effect from 1943, reached their first peak. The fact that Würzburg had been spared for so long, while numerous other German cities, notably Hamburg, Berlin and Dresden, were already in ruins, fueled hopes that the city, with only a few war-related industries, might be spared a massive attack. This mood was mixed with irrational rumors, such as that of Winston Churchill studying at Würzburg University, which meant that the city would be spared a fate like that of Dresden. Isolated smaller attacks since February, however, soon diminished this hope. The constant air alarms had been part of everyday life for some time.

From May 1944, the university was connected to the air-raid warning network to allow teaching to continue, as evacuation only became necessary in the event of an acute threat situation. As the front steadily approached, the warning period shortened, but the frequency of the attacks increasingly increased, so that regular operation of the university was no longer conceivable at the beginning of 1945. Fortunately, the winter semester 1944/45 had already ended on February 28. 1,768 students had still been enrolled in this last semester of the war. Thus, the university lay largely deserted when the devastating bombing raid by 280 Royal Air Force planes began at 9:20 p.m. on March 16, 1945. It lasted twenty minutes, but the ensuing firestorm was to destroy 90% of the old city in the hours that followed and cost the lives of some 5,000 people.

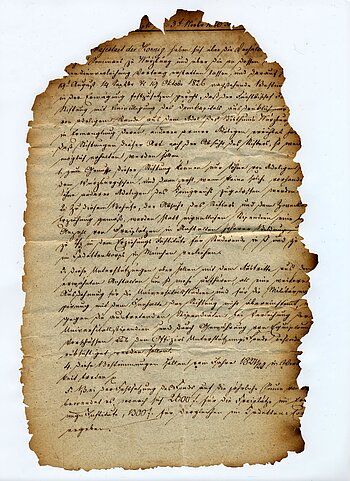

Most of the university buildings also fell victim to the bombing. One of the hardest hit was the New University on Sanderring, which was largely burned out. In particular, the main building and the east wing were destroyed except for the outer walls and parts of the basement, so the theological and the law and political science faculties had lost their facilities and seminar libraries. In the Faculty of Philosophy, the photographic holdings of the Institutes of Art History and Archaeology had been preserved. The west wing and thus the English and Romance departments with their libraries and furnishings as well as the German Department were partially spared. The observatory was completely destroyed. The registry rooms of the Administrative Committee and the University Treasury were also lost on March 16. A large part of the historical files stored in the New University were lost to the flames that night. The forces unleashed by the firestorm were so immense that a piece of file material from the university's archives, a letter from King Ludwig I dated November 3, 1826 (see illustration), was carried more than 50 km through the air and rained down in the Steigerwald the following day. Further losses of records and office equipment occurred in the following weeks through devastation and looting because the doors of the archive and storage rooms could not be locked.

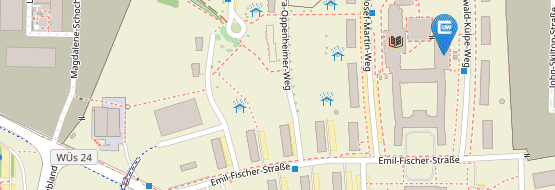

The buildings of the natural science institutions and institutes in the Roentgenring area suffered only minor damage, in contrast to the Zoological and Geographical Institutes in Klinikstrasse, which suffered severe bomb damage. With the exception of the mathematical library housed in the New University, the natural science libraries survived the attack.

The Luitpold Hospital on the outskirts of the city also survived the attack comparatively well. Although numerous roof trusses were a victim of the flames and some upper floors were burned out and windows and doors damaged, the furnishings were still largely available, so that the clinics were able to continue their essential operations. Only a few institutes in Koellikerstrasse (the Anatomical, Pharmacological and Physiological-Chemical Institutes) and the Institute of Hereditary Biology (Klinikstr. 6) were more severely affected.

The University Library in the Old University was also severely affected, having been unable to move parts of its holdings and losing about 200,000 books and 250,000 dissertations. Parts of the collections of the Martin von Wagner Museum were preserved, but the university history collection was burned.

The image of the university immediately after the war is illustrated by a memory of Professor Werner Wachsmuth, who showed the ruins of the university to a member of the Lower Bavarian state parliament, who, on seeing the new university, said: "I moan, wia reiß'm des ganzen Glump hier zamm und stöin's in Rengschburg wieda auf". This statement may sound amusing, but the relocation of the University of Würzburg after the war was an option that was actually discussed and will be examined in the next article.

Author: Marcus Holtz