How one photon becomes four charge carriers

04/14/2023Some materials convert photons into more free charges than would be expected. Using an ultrafast film, researchers have now been able to get a picture of this process. Physicists from the University of Würzburg were also involved.

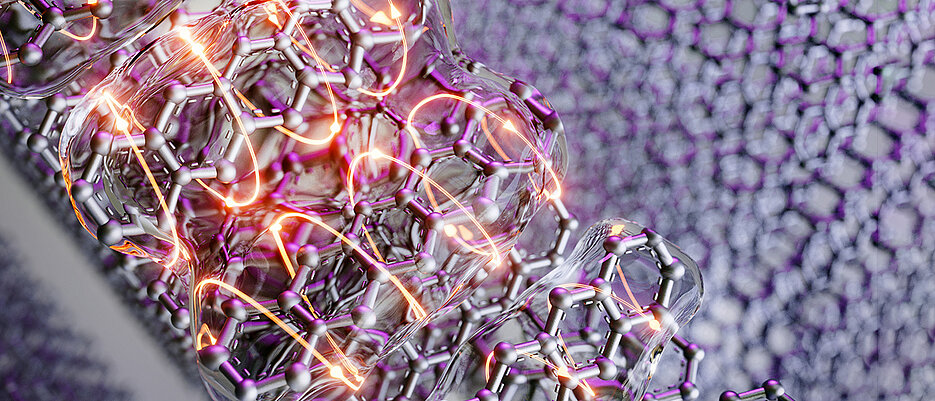

Photovoltaics, the conversion of light to electricity, is a key technology for sustainable energy. Since the days of Max Planck and Albert Einstein, we know that light as well as electricity come in tiny, quantized packets called photons and elementary charges, the latter represented by electrons and holes.

Better solar cells thanks to exciton splitting

In a usual solar cell, the energy of a single photon is transferred to two free charges in the material, but no more than that. However, a few molecular materials like pentacene are an exception and show conversion of one photon into four charges, instead. This excitation doubling, which is called exciton fission, could be extremely useful for high-efficiency photovoltaics, specifically to upgrade the dominant silicon-based technologies.

A team of researchers at the Fritz Haber Institute of the Max Planck Society, the Technical University of Berlin, and the Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg have now deciphered the first step of this process by recording an ultrafast movie of the photon-to-electricity conversion process, resolving a decades-old debate about the mechanism of the process.

”When pentacene is excited by light, the charges in the material rapidly react,” explains Prof. Ralph Ernstorfer, a senior author of the study. “It was an open and highly disputed question whether an absorbed photon excites two electrons and holes directly or initially just one electron-hole pair, which subsequently shares its energy with another charge pair.” Ernstorfer is head of a Max Planck research group at the Fritz Haber Institute and Professor of Experimental Physics at the Technical University of Berlin.

Snapshots of one billionth of a millionth of a second

To unravel this mystery the researchers used time- and angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy, a cutting-edge technique to observe the dynamics of electrons on the femtosecond time scale, which is a billionth of a millionth of a second. This ultrafast electron movie camera enabled them to capture images of the fleeting excited electrons for the first time.

“Seeing these charge carrier pairs was crucial to decipher the process,” says Alexander Neef, from the Fritz Haber Institute and the first author of the study. “An excited electron-hole pair not only has a specific energy but also adapts distinct patterns, which are called orbitals. To understand the process of singlet fission it is such essential to identify the orbital shapes of the charge carriers and how these change over time.”

Crucial for the use of organic semiconductors

With the images from the ultrafast electron movie at hand, the researchers decomposed the dynamics of the excited charge carriers for the first time based on their orbital characteristics. “We can now say with certainty that only one electron-hole pair is excited immediately after photon excitation and identified the mechanism of the free charge carrier-doubling process,” adds Alexander Neef.

‘Resolving this initial step in exciton fission is essential to successfully implement this class of organic semiconductors in innovative photovoltaic applications and, thus, to further boost the conversion efficiency of today’s solar-cells’ states Prof. Jens Pflaum, whose group at the University of Würzburg has provided the high quality molecular crystals for this study. Such an advance will have enormous impacts as solar energy and its generation by these third-generation cells will be a dominant energy source of the future.

Original publication

Orbital-resolved observation of singlet fission. Alexander Neef, Samuel Beaulieu, Sebastian Hammer, Shuo Dong, Julian Maklar, Tommaso Pincelli, R. Patrick Xian, Martin Wolf, Laurenz Rettig, Jens Pflaum & Ralph Ernstorfer. Nature, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-05814-1

A Nature-Comment you can find here: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-023-00980-8

Contact

Prof. Dr. Jens Pflaum, Lehrstuhl für Experimentelle Physik VI, T: +49 931 31-83118, jpflaum@physik.uni-wuerzburg.de