From Würzburg into the world

04/30/2017Johannes Obergfell came across the topic of migration thanks to his magister thesis. Today, he works at the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees. A "smoky office" is one of his prominent memories of his time at university.

Which jobs do graduates from the University of Würzburg work in? To present different perspectives to students, Michaela Thiel, the director of the central alumni network, has interviewed selected alumni. This time, it is Dr Johannes Obergfell's turn. Obergfell works with the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF) in Nuremberg. He studied political science, economic geography and European ethnology in Würzburg.

Dr Obergfell, you were already interested in migration long before the recent refugee wave. Why did you choose this topic? My year abroad in Guadalajara in Mexico in 2007/2008 and the impressions I gathered there have had a lasting impression on me. Migration is an omnipresent issue there. Almost everybody has made migration experiences or has close relatives or friends who have done so. But originally, I wanted to write my magister thesis on the 'drug war'. However, I was advised against doing on-site research for reasons of safety. So I chose the obvious topic of 'migration' for my magister thesis.

How did you approach the subject? In 2009, I revisited Mexico for several months and conducted interviews, among others with representatives from political parties. In light of the political course the US is taking towards Mexico as well as migration and migrants from Latin America, my old magister thesis still seems relevant: unfortunately a lot of the issues discussed back then are still, or rather again, on the political agenda.

And afterwards you stayed with the topic. Yes, my doctoral thesis was about 'migration out of Germany into Turkey'. A lot of young people of Turkish origin, some of whom are highly qualified, turn their backs on Germany because they don't feel accepted here, believe to have worse employment perspectives and feel discriminated. Although the topic of 'immigration' dominates media reporting, migration out of Germany is still relevant and happening and should not be lost sight of.

Migration and refugees are discussed intensively at present. How has the discussion changed over the past months in your view? People are concerned about migration and especially about the migration of refugees. Before 2015, the crisis regions of our world seemed far away for many people. But after autumn 2015 at the latest, the situation changed when the consequences of war, famine and suffering began to manifest themselves in the form of migratory movements at German border crossings that were no longer restricted to Greece and Italy – which weren't so remote either after all.

What role does migration play in your personal life? For most of us, migration plays a central and significant role, unconsciously for some part. I was an educational migrant in Mexico myself and I could be characterized as an economically motivated domestic migrant given that I am not originally from Franconia. In my family and private environment, national and international migration experiences are common. Migration is not abstract or new, rather it is a normal process that is probably as old as humanity itself. Through my work at the BAMF, I am very close to the action and I get insight into many processes. My private environment is interested in that.

What do you respond to people who say that they are afraid of the many refugees? I usually start by asking them whether they have already seen a lot of refugees and with how many they have had contact. They usually answer: 'Neither'. Frequently, their fears are unfounded; they are reactions to stereotypes or hearsay which I try to clarify.

And what if people don't want refugees to live in their neighbourhood? There are refugee families living next door and I have not had any negative experiences with my new neighbours so far. You can talk about a lot of things if necessary – even language barriers can be overcome. We can find solutions for many problems whether our neighbours are from Syria or Upper Bavaria.

But still many people who help refugees are sometimes harshly criticized. I don't like either of the terms 'Gutmensch' (do-gooder) or 'Wutbürger' (angry citizen) because they paint the world in black and white. Fortunately, real life is much more colourful. I have no tolerance for violence, crimes and disrespect regardless of someone's origin or nationality. It is the job of the police and judges or rather of the law to equip the police properly. And of course we should all treat each other in a civilized manner.

German asylum law is criticized for being too idealistic by some, while others find it too restrictive. What's your opinion on this? Granting asylum certainly involves challenges and tests us as citizens and as a society, but I see the frequently stated cost-benefits calculation in a critical light. Asylum is rooted in our constitution and for a good reason. I advise empathy and when talking to people I often ask them: 'What would you do if your whole existence at home was destroyed by bombs, if you had lost family and friends, if you could no longer provide for your family in a refugee camp in Jordan because the industrialized nations are not willing to grant you, your wife and small children one dollar per day for water and food? Would you stay in the war zone and wait for the next bullet to hit your daughter or yourself? Would you wait in the refugee camp for your children to starve? Where would you go? To some place where you would have to live on the street as someone who has no rights? Or would you go to Germany where you will have a roof above your head, where your family will get medical care and where you can become part of the society also because you have access to integration courses that allow you to learn the German language?'

What do your everyday activities at work involve? I am lucky to work in a field where no two workdays are exactly the same. We prepare a lot of appointments for our agency management, give presentations, analyse agency-relevant social and political lectures and also do conceptual work in fundamental matters. I read a lot, write a lot and communicate a lot, a combination I like.

What would you recommend to students who are interested in working at the BAMF? They should inform themselves in depth about the various departments of the Federal Office. The public frequently perceives us 'only' as the 'asylum office', which is not quite correct. With some 9,000 employees, we are a large institution that offers countless exciting fields of activity from asylum matters to integration and research, radicalisation prevention, digitisation, public relations and many more. Browse through the information provided at www.bamf.de and get an idea of the variety of operations by taking a look at the Federal Office's organisation chart.

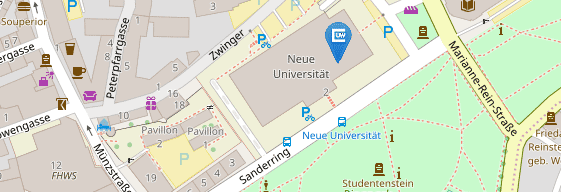

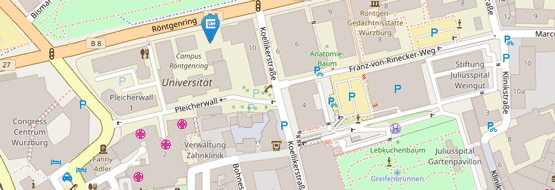

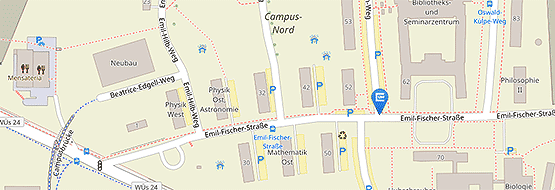

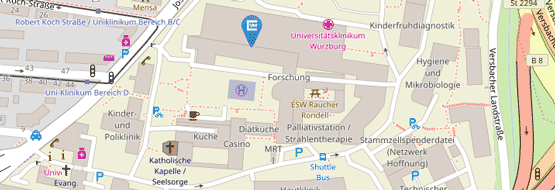

What are your best memories of your time as a student? The moment I put my magister thesis in the department's letterbox. The certificate presentation ceremony in the Residence was also great just as participating in the NMUN simulation game of the United Nations. I had a great time studying in Würzburg despite the dilapidated building at Wittelsbacherplatz, overcrowded rooms at Hubland and a shortage of lecturers. As a magister student you have sufficient freedom and time to listen to interesting lectures from other departments as a guest student, actively design your own studies and enjoy life as a student. I will never forget the smoky office of Professor Christoph Daxelmüller, who died much too early unfortunately, and the trip to Naples with him.

Thank you for the interview.