Ingroup experiences improve attitudes towards outgroups

09/06/2022A realistic assessment of our own social group can help improve our attitude towards other groups. This is shown by a new study by the University Hospital of Würzburg.

We are us, and others are exactly that – other. The feeling of belonging to a particular group that is clearly different from other groups is probably a human trait that we all share. Associated with this are usually equally clear notions about how others differ from us: 1b are all nerds, according to 1a; women are rubbish at parking, men say; Spaniards are never on time, Germans believe.

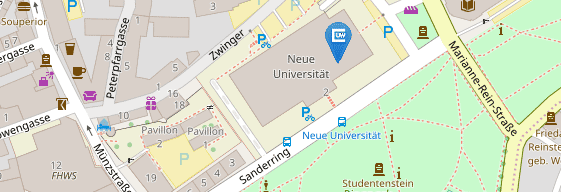

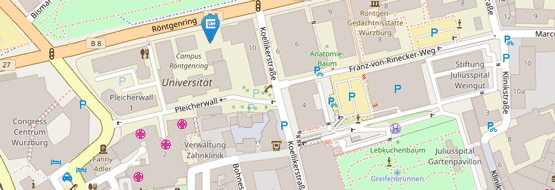

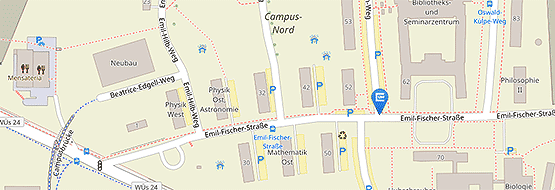

How such prejudices – or to put it more neutrally – this form of bias can be influenced has now been investigated by a team of neuroscientists from Germany, the Netherlands and Switzerland. This study was the responsibility of Grit Hein, Professor of Translational Social Neuroscience at the Department of Psychiatry, Psychosomatics and Psychotherapy at the University Hospital of Würzburg, and Philippe Tobler, Professor of Neuroeconomics and Social Neuroscience at the University of Zurich. The team published the findings of their research in The Journal of Neuroscience.

New experiences change the assessment

“Our study shows that a realistic assessment of the traits of the members of a group to which you feel you belong contributes to less pronounced favouritism towards your own group over others,” is how Hein explains the core finding of their research. Or, to put it another way, if you are aware that not everything is perfect in your own group – the ingroup – you will not be so quick to form a negative opinion of others.

However, that is only one part of the findings that have now been published. Hein and her team were also interested in how such a realistic assessment can be achieved: by learning from experiences with members of the other group or perhaps through new – and possibly more realistic – experiences with the seemingly close ingroup.

Here too the study reveals a clear result: “Although our test subjects learnt from experiences both with their own group and with the outside group, the new experiences with their own group had a stronger effect. If these experiences were negative, this reduced the favouritism towards their own group compared to the outgroup. The stronger the identification is to begin with, the more pronounced this reduction is,” explains the neuroscientist.

A study with two groups

The study was conducted at the University of Zurich. A group of Swiss participants met a group whose families came from the Middle East. The Swiss test subjects were informed that they would receive painful stimulation on the back of the hand via an electrode during the experiment. However, one of the people present, either a Swiss person or someone with a Middle Eastern family background, could prevent the stimulation. But this would mean foregoing money that this person would otherwise receive.

In reality, though, the course of the experiment was “manipulated” at this point. “In principle, the painful shock did not happen in 75% of all cases, regardless of whether members of the ingroup or the outgroup were supposed to prevent it,” explains Grit Hein. Accordingly, the objective experiences for the test subject with the electrode were the same and predominantly positive in all cases with both groups.

Questions about likeability and group membership

What is the impact of this experience? The answers the participants gave to a questionnaire that they had to complete both before and after the learning experiment gave clues to this. This questionnaire included questions about group membership (“What would be the chance that you would use the word ‘we’ to describe yourself and these people?”), about similarity (“How much do you have in common with these people?”) and about likeability (“How comfortable do you find the idea of meeting these people in the future?”).

The evaluation also included ratings by the test subject during the experiment in relation to how much they were expecting a painful stimulation after being informed by the experimenter which of the two groups could prevent their pain during that particular trial – the Swiss group or the group with a migrant background.

Clear patterns of activity in the brain

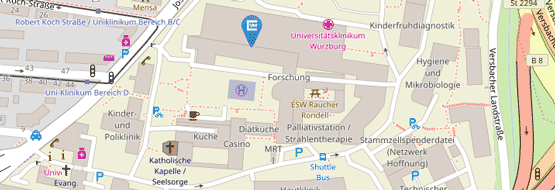

While the test subjects received help from a member of the ingroup or the outgroup, their neural responses were recorded using an MRI scanner.

The results showed that the change in assessment of the ingroup and outgroup is accompanied by a change in interaction between two specific areas of the brain: “At the neural level, these processes were related to the coupling between the left inferior parietal lobule and the left anterior insula, in other words regions that are associated with the updating of impressions,” explains Grit Hein.

Important evidence for the shaping of social impressions

Grit Hein summarises the outcome of the study by saying: “Our findings show that we learn from experiences with members of the ingroup and outgroup and how these experiences shape our attitude towards these groups.” They demonstrate the learning processes and neural processes that underlie dynamic changes in attitudes through experiences.

So, when people have experiences that do not match their expectations, their opinion about people who belong to an outgroup aligns with their opinion about the members of the ingroup. A realistic assessment of their own group is therefore a promising strategy for reducing favouritism, which is an insight that could have practical implications for the improvement of relations between groups.

Original publication

Learning from Ingroup Experiences Changes Intergroup Impressions. Yuqing Zhou, Björn Lindström, Alexander Soutschek, Pyungwon Kang, Philippe N. Tobler and Grit Hein. Journal of Neuroscience, 29 July 2022, JN-RM-0027-22; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0027-22.2022

Contact

Prof. Grit Hein, PhD, Professor of Translational Social Neuroscience, University and University Hospital of Würzburg, T: +49 931 201-77411, hein_g@ukw.de