Beetles Cooperate in Brood Care

11/04/2020Ambrosia beetles are fascinating: they practice agriculture with fungi and they live in a highly developed social system. Biologist Peter Biedermann has now discovered new facts about them.

They belong to the bark beetle family, and they are the only animals in nature, along with leaf-cutter ants and some termites, that practice agriculture: ambrosia beetles. These insects, which are about two millimetres in size, carry fungal spores into their nests and sow them in specially created tunnels in the wood. They then care for the growing fungal cultures that serve as food for them.

Like farmers, the beetles also have to defend their fungal cultures against pests, such as other fungi that threaten to overgrow the gardens. Individually living beetles could hardly manage this work. This is why ambrosia beetles have developed sophisticated social systems over the course of evolution, similar to those of bees and other social insects. "This is unique in beetles," says Würzburg biologist Peter Biedermann.

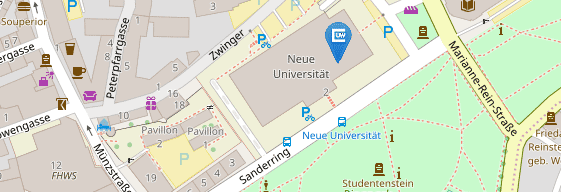

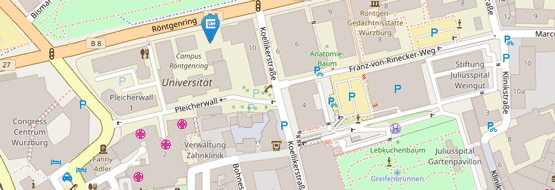

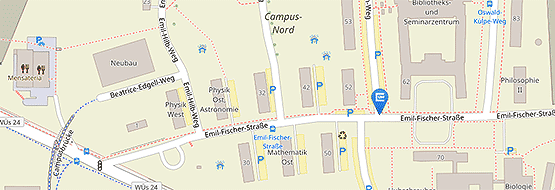

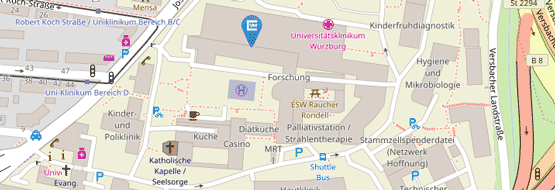

Biedermann is fascinated by ambrosia beetles. He studied them at the Biocentre of Julius-Maximilians-Universität (JMU) Würzburg in Bavaria, Germany. "Because they have been practicing this type of sustainable agriculture for 60 million years, I am interested in how they combat harmful fungi. Perhaps we can learn from the beetles for our own agriculture".

Fascinating social system discovered in second beetle species

Ambrosia beetles are spread all over the world. In the case of the Fruit-tree pinhole borer (Xyleborinus saxesenii) native to Europe and invasive worldwide, Biedermann described an extraordinarily highly developed social system already in 2011 (publication Biedermann & Taborsky, PNAS). He has now found a similar social system in the sugercane shot-hole borer Xyleborus affinis, which lives in the tropics of the Americas. No other beetles with this peculiarity are known so far.

Biedermann presents his new findings on the social system of the American beetle in the magazine Frontiers in Ecology & Evolution: After a beetle mother has established a new nest with fungal gardens and the first offspring develops, many young beetles stay with their mother for the time being. They help her to care for the fungi and to raise the offspring.

Female workers can reproduce

This is comparable to the workers of the bees. "In contrast to the sterile bee workers, however, the female beetle workers are capable of reproduction: depending on their life situation, they decide whether they will eventually establish their own nest, whether they will lay eggs in the birth nest themselves or whether they will exclusively help the mother," says the biologist.

This social system is termed cooperative brood care, which is very rare in nature and is a preliminary stage to the eusocial system of social insects with their sterile workers and a fertile queen. These beetles could help science to understand the evolution of sociality.

Abundance of "weed fungi" determines activity

In his study, Biedermann has also discovered new information about the sugercane shot-hole borers farming activities. The beetles adjust their fungal care behaviour according to whether there are many or few "weed fungi" growing in the nest. Furthermore, it was shown that beetle daughters who do not reproduce themselves help with the work in the nest, but otherwise show less social behaviour than their egg-laying sisters.

Peter Biedermann recently took over the professorship for forest entomology and forest protection at the University of Freiburg in Germany. His next step there will be to investigate whether ambrosia beetles can distinguish between weedy and food fungi on the basis of their odour and how the beetles selectively weed or chemically control the fungal weeds.

YouTube-Video about the ambrosia beelte

Publication

Cooperative Breeding in the Ambrosia Beetle Xyleborus affinis and Management of Its Fungal Symbionts. Peter Biedermann, Frontiers in Ecology & Evolution, Open Access, 4 November 2020, DOI: 10.3389/fevo.2020.518954

Funding

This research project was financially supported by the USDA Forest Service, the Austrian Academy of Sciences and by the Emmy Noether program of the German Research Foundation DFG. The University of Würzburg financed public access to the article through its Open Access publication program.

Contact

Prof. Dr. Peter Biedermann, Chair of Forest Entomology and Forest Protection, Albert-Ludwigs-University Freiburg, T +49 0761 203-54111 or 203-54112, peter.biedermann@forento.uni-freiburg.de

Website: www.insect-fungus.com