Young embryo devours dangerous cell

05/16/2018Researchers at the University of Würzburg have been able to show how embryos dispose of the life-threatening leftovers of egg maturation.

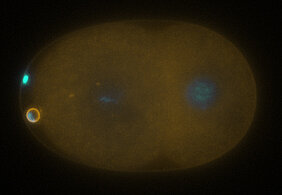

Embryos from the nematode worm C. elegans have an important task to accomplish as early as an hour after their formation. They "eat" the leftovers of egg maturation that could otherwise be life-threatening for them. Scientists at the Rudolf Virchow Center at the University of Würzburg have now demonstrated this using time-lapse microscopy. Their results could improve the understanding of the molecular mechanisms behind autoimmune diseases.

Similar to human embryos, the life of a new nematode worm begins with the fusion of an egg and a sperm cell. Around the same time as this fusion, the egg cell undergoes its last developmental steps. In doing so, the egg cell buds out two tiny miniature cells, the so-called polar bodies.

One of the polar bodies remains in direct contact with the embryo. And this is a significant problem. "The polar body contains substances that can be very dangerous for the young embryo, including chemical signals, destructive enzymes and even the contained DNA," explains Dr. Ann Wehman, in whose lab the study was carried out. "The embryo must prevent this content from being released in its environment."

How such a young embryo could do that, was previously unknown. Wehman, together with her coworkers Dr. Gholamreza Fazeli, Maurice Stetter and Jaime Lisack, were able to solve this puzzle. "We were able to show that the early embryo takes up the polar body and digests it," says Wehman. "We knew that there are specialized immune cells that can do this – so-called phagocytes. However, these worm embryos are still at the very beginning of their development; they only consist of a few cells themselves."

The polar body sends distinct "eat me" signals from its surface. These cause the cell membrane of the embryo to surround it. The entire polar body is then contained in a membrane-wrapped inclusion called a phagosome, which is a type of intracellular garbage bag. Once enclosed, certain enzymes destroy the membrane of the polar body. Since the encircling phagosome membrane remains intact, the content released from the polar body is still protected inside the embryo and therefore cannot harm it.

After a few hours the polar body is digested

"In the next 30 minutes, the DNA is degraded," explains Wehman. "Meanwhile, the rest of the polar body is mechanically stretched and broken into numerous pieces. These smaller fragments are easier to digest." Overall, the process takes less than two hours. Then the entire polar body is consumed and its dangerous content is rendered harmless.

"This process is almost identical in all C. elegans embryos," says Wehman. "We were able to film the process in high temporal resolution and thus make each step fully visible."

This study could help to improve the understanding of human autoimmune diseases. Degradation of damaged cells and cell fragments is impaired in the inflammatory skin disease lupus erythematosus, for example. Using the polar body as a model, researchers can now investigate these important degradation processes in more detail.

Publication

Gholamreza Fazeli, Maurice Stetter, Jaime N. Lisack und Ann M. Wehman: C. elegans blastomeres clear the corpse of the second polar body by LC3-associated phagocytosis; Cell Reports; DOI: 10.1016 /j.celrep.2018.04.043

Person

Dr. Ann Wehman moved to Germany in 2013 to lead a research group in the Rudolf Virchow Center for Experimental Biomedicine at the University of Würzburg. Website Wehman Group

About the Rudolf Virchow Center

The Rudolf Virchow Center is a central institution of the University of Würzburg. All research groups are working on target proteins, which are essential for cellular function and therefore central to health and disease.

Contact

Dr. Ann Wehman (Rudolf-Virchow-Zentrum)

Tel. +49 (0)931-31-81906, ann.wehman@uni-wuerzburg.de

Dr. Daniela Diefenbacher (Pressestelle, Rudolf-Virchow-Zentrum)

Tel. +49 (0)931 3188631, daniela.diefenbacher@uni-wuerzburg.de